Jonathan Dimbleby is right – to understand the war in Ukraine, look to 1944

It’s uncomfortable to reflect that 80 years ago we had reason to be very thankful to the Russians for displaying on the Eastern Front the same characteristics we find so abhorrent in their conduct in Ukraine today. Chief among them is their pitiless treatment of their opponents, soldier and civilian, along with an apparently inexhaustible willingness to die.

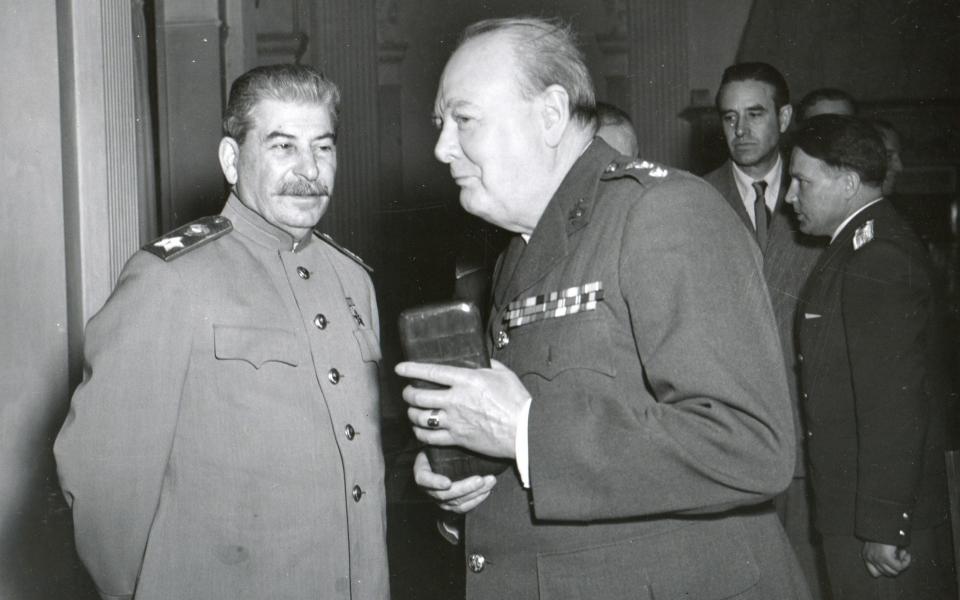

The truth, as Stalin never failed to point out, was that from June 1941 until D-Day, it was the Red Army that did most of the fighting in the struggle against Hitler. The fact that he and his fellow dictator had essentially been allies for the first third of the war was of course ignored.

The Soviets were fighting for their own survival, not ours, but for a few short years, overwhelming mutual interest ensured that the stars of capitalism and communism were aligned. The Western allies certainly contributed mightily to victory. However, without the Soviets’ resilience and almost unimaginable sacrifices in what Jonathan Dimbleby here describes as “the bloodiest and most brutal mega-conflict in the annals of human warfare” history would have turned out very differently.

The historiographical trend of recent decades has been to redress the earlier Eurocentric focus of English-language historians and accept that the Eastern Front was the crucial theatre where Hitler’s armies were broken and the war effectively won. Endgame 1944’s subtitle – How Stalin Won the War – advertises the author’s intention to push perceptions further down this path.

While most Brits have heard of Operation Overlord and will be hearing much more in the coming weeks with the 80 anniversary of D-Day, few know the significance of Bagration – the Soviet offensive that began just two weeks later. They should, and Endgame: 1944 is a great place to learn about it. Dimbleby tells the story of the titanic operation well, swooping from panoramic strategic overview to harrowing close-ups of the battlefield reality drawn from a rich fund of individual accounts.

Named, tellingly, after a warrior prince, a Georgian like Stalin who was mortally wounded fighting Napoleon at Borodino, Bagration was designed to sweep the German invaders out of Soviet territory and back to Berlin. As well as avenging the humiliation of Operation Barbarossa, it had a grand political purpose: to redraw the map of eastern Europe to ensure Soviet domination and create a buffer zone to remove the threat of history repeating itself. If it suceeded the western Allies would be powerless to oppose the new strategic reality. So while smashing the Nazis, Bagration would lay the foundations for the Cold War.

In the spring of 1944 the Germans were everywhere on the defensive and Stalin and his generals were weighing their options for the best way to finish them off. The Red Army was very different from the demoralised and shambolic force that had all but collapsed under the onslaught of Barbarossa three years before. Unlike Hitler, Stalin learned from his mistakes, and now allowed his commanders a degree of freedom. So it was that when General Konstantin Rokossovsky defied the Red Tsar and insisted on a two- rather than one-pronged attack on the Belorussian front at the heart of the German defence line, instead of being dragged off and shot he was given his head – with triumphant results.

Bagration fell on the Germans like an avalanche – of armour, aircraft and manpower, which the Soviet generals squandered with their habitual abandon. But the plan also made brilliant use of maskirovka – deception operations involving dummy tanks, fake troop movements and signals traffic that constantly wrong-footed the enemy. It was an almost complete success. Between June 22 and August 19, 28 of the 34 divisions of Army Group Centre were destroyed and the German front line shattered.

The Germans knew the assault was coming but had no idea where the main blow would fall. They were further hampered by Hitler’s senseless “stand-fast” orders which left no room for manoeuvre.

The huge defeats of the opening weeks mirrored the catastrophes that befell the Soviets in 1941. The fighting was merciless, the Red Army’s thirst for blood sharpened by the atrocities they encountered everywhere they advanced. Everyone was well used to slaughter by now but the scenes they witnessed still induced a terrible awe. “Nowhere else have I seen such an enormous number of German corpses” wrote one veteran. “The road was literally lined with them… in all sorts of poses and positions. I got so fed up with looking at them that I felt sick.”

There was worse to come. On July 24 units of the Eighth Guards Army reached Lublin and discovered in the suburbs the Majdanek murder factory. The speed of the Soviet advance had left the SS no time to destroy the evidence of their evil and for the first time the world had tangible evidence of the Holocaust.

War is hell but the Eastern Front was the very depths of Hades. It was the civilians who suffered most, caught in the ebb and flow of the fighting, preyed on by successive conquerors as well as the partisan bands who harrassed the German rear areas with considerable effect.

Nonetheless, the war was the Soviet Union’s finest hour. Under Stalin, its people had rid the world of the Nazis and established the Motherland as a global power.

As the author points out, in the confusion and humiliation of the collapse of communism, the masses looked back on the Great Patriotic War – and even Stalin – as a comforting memory. It is a mindset that Vladimir Putin has ruthlessly exploited to provide the twisted narrative for his own war in Ukraine.

One of the strengths of this book is the line it draws between the awful then of 1944 and the grim events of today. The Russians’ actions in Ukraine, writes Dimbleby “may be deplorable but they are not inexplicable: they did not emerge from a void.” Endgame 1944 is thus as much a primer for the present as it is sound history.

Patrick Bishop’s Paris ’44: The Shame and the Glory is out in July. Endgame 1944: How Stalin Won The War is published by Viking at £25. To order your copy for £19.99 call 0808 196 6794 or visit Telegraph Books