There’s One Part of Brittney Griner’s Account of Life in Russian Prison That Really Stands Out

I would watch a show where Tucker Carlson interviews Brittney Griner. It might be fun to see the cable-TV star squirm before the openly lesbian 6-foot-7 basketball player as she schools America’s leading Kremlin apologist on the realities of Vladimir Putin’s Russia that he missed during his slack-jawed tour of Moscow’s lavish subway stations and grocery stores.

At one point in Coming Home, Griner’s new memoir of her forced stay in Russia for most of 2022, the nine-time WNBA All-Star and two-time Olympic gold medalist quotes Nelson Mandela’s words: “No one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails.” By that measure, Griner knows Russia as well as almost any American.

Mandela’s remark appears as the epigraph for a chapter titled “Slave Camp,” which aptly describes the prison where Griner spent most of her 293 days in Russian lockups for the crime of accidentally bringing into the country two vape pens containing a total of 0.7 grams of medically prescribed cannabis—which prosecutors characterized as a “significant amount of narcotics.”

She later learned that, in half of Russia’s 36 trials that year for the same crime, the defendants received suspended sentences. But Griner had the misfortune of being sniffed out by airport security dogs two weeks before Putin invaded Ukraine. By the time her trial came up, she “wasn’t just another prisoner,” as she puts it, but a “chess piece in a showdown between superpowers.” Where usually some deal is worked out with a local official, Griner’s case “was already at the Kremlin.”

The Biden administration formally declared her case one of “wrongful detention,” meaning it was put in the hands of a State Department office authorized to bargain with foreign governments for an American citizen’s release. Griner’s Russian lawyer (a decent young man who spoke English well and loved rock ’n’ roll) urged her to plead guilty—Putin wouldn’t consider her release if she argued that his henchmen were mistaken. So she did, while also insisting that she didn’t mean to bring drugs into the country. (She’d left the house in a hurry, without emptying her bag from a prior trip.) “Kissing the king’s ring,” she writes, “was my fastest way to freedom.” So she thought.

But by this time, her arrest was international news. Putin and the Russian court system were in the spotlight. As a result, the trial judge denied Griner’s request for bail or house arrest, instead sentencing her to nine years of hard labor.

The sentence was close to the maximum possible. Even the jaded courthouse officers were shocked. “One of the guards gasped,” Griner writes. “The translator swallowed hard before whispering the sentence to me.”

She was sent to Corrective Colony No. 2, also known as IK-2, in Mordovia, more than 300 miles from Moscow. IK-2 was once a link in the chain of Stalin’s monstrous gulags, and it seems the monsters in charge there now never got the message that those times have passed. The guards at the gate met her cohort of new inmates with AK-47s pointed straight at them and German shepherds barking at their sides. The warden, one of Griner’s fellow prisoners told her, had tortured a female inmate at another prison and, instead of being fired, was transferred to IK-2.

The bathrooms, lacking hot water and encrusted with filth, were “a special hell.” Outdoor morning exercises were mandatory, even in blizzards. At one point of her stay, the prison lost electricity for three days; everyone froze in the dark. Privacy and dignity were absent, humiliation was constant.

IK-2 is called a “labor camp” for a reason. Griner and her cell-neighbors worked “10-, 12-, or 15-hour days, around the clock,” she writes, in a sweatshop-like chamber with no ventilation or heat and no bathroom breaks beyond short mealtimes. Her job was cutting fabric and sewing buttons for Russian military uniforms with fellow inmates—a quota of 500 uniforms a day. For the towering Griner leaning over a low table, the labor was not just punishing and exhausting but back-wrecking.

In the end, her guilty-plea strategy, along with persistent bargaining by the State Department, paid off. She was traded for the Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout, who had served a little less than half of a 25-year sentence in a U.S. federal prison for selling weapons to terrorists. (Biden was criticized for the trade, but—though this isn’t mentioned in her book—even the judge who sentenced Bout said his 11 years of time served fit the crime.)

When the Russian plane carrying Griner to freedom touched down in Abu Dhabi, and she walked across the tarmac to board the American plane that would take her home, she crossed paths with Bout, walking in the opposite direction. The man whose nickname was “the merchant of death” nodded his greeting and shook her hand. “Unlike my bruised hands,” Griner noticed, “Viktor’s hands were soft. So were the creases on his face. He’d spent much of his sentence doing artwork, I’d heard—painting portraits of cats. I’d spent mine with a table saw.”

It was the final, most ironic moment of sharp contrast between Griner’s homeland and the country of her imprisonment. The contrasts serve as a major theme of the memoir—a message she might not have noticed, much less highlighted, had she not been put through the Russian system.

Before her arrest, Griner spent the offseasons of eight years in Russia, a place she’d come to regard as her “second home.” She was the star of the Ekaterinburg women’s basketball team, which was the EuroLeague champion. She was “sports royalty,” recognized on the streets, and well paid (earning $1 million per season, five times as much as her WNBA salary, the reason she and many other female American athletes play overseas). But, as she later realized, the club owners had kept her and her teammates in a “bubble,” which “kept a lot of the real Russia out of view.”

The segment of real Russia that she would come to know too well emerged all too clearly the moment she was first detained—in a “cold cell” barely as wide as she was tall, adorned with only a dim lightbulb and a camera. The food was “inedible”; the harassing guards viewed her as “a freak show to liven their shift.”

The indignities mounted at the court hearings. As the Boston Globe’s Moscow reporter in the 1990s, I covered a few criminal trials and was startled to see the defendants escorted into a cage off to a corner of the courtroom, their lawyers kept outside the bars. Griner was shocked as well. This was, and apparently still is, standard procedure. The message is clear: You are already deemed guilty—a premise confirmed by the conviction rate, which for drug-related crimes was 99.9 percent.

Griner’s Russian lawyer presented evidence at the trial showing that her arrest violated several procedural laws and the chemical analysis of the vape cartridge was incomplete (an official claimed that he ran out of paper). A defendant in almost any American court would be let go on these challenges. Griner’s judge, a stern woman, was unmoved; she had her orders.

Before her fateful last trip to Russia, Griner had been an outspoken critic of American injustices. Like many Black athletes, she kneeled at the start of games during the national anthem in protest of the Black men killed by police. During the 2023 season, after she got back, she writes, “I stood for the national anthem, teared up at its new meaning for me.” She explains, “I stood proudly for the reason I once knelt, because I cherish my homeland.” One’s attitude toward the object of protest changes “after being imprisoned in a country where public dissent can get you killed.”

Not that coming home was all peaches and cream. The slave labor, poor nutrition, and binge smoking (to relieve the stress) left her anemic and dehydrated; it took her months to recover enough strength to get back on the court, and even then, as she puts it, she played “like crap.” Her team, the Phoenix Mercury, usually top-seeded, finished her return season in last place.

She experienced nightmares and flashbacks, suffered from anxiety and angst, felt estranged from her loved ones and her surroundings. “Russia,” she writes, “stripped me of my humanity … sadness was popping all over the place.” Still, by the book’s end, things were getting better. She’d turned to religion while in prison; it still provided some calm. She also became active in Bring Our Families Home, a group that lobbies on behalf of the 57 Americans wrongfully in foreign jails who are “as desperate as I once was.” Reading this book deepens the sorrow of wondering about the lives of Paul Whelan and Evan Gershkovich, the two most prominent Americans unjustly serving time in Russian prisons today. (Griner had the good fortune to be able to plead guilty, thus easing the process of a trade; her sentence was crazily excessive, but she did commit the crime even if unintentionally. Whelan and Gershkovich, both charged with espionage, did not.)

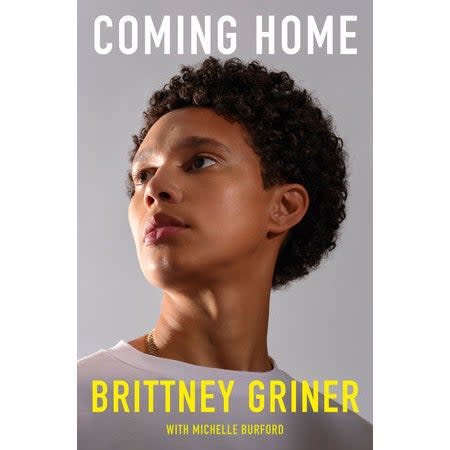

Griner wrote Coming Home with Michelle Burford, a frequent collaborator on bestselling memoirs, especially by Black women (Oprah Winfrey, Cicely Tyson, and Alicia Keys, to name a few), and Griner chose well. The chapters depicting the courtroom and prison are truly gripping; the ones about her homecoming are genuinely moving. They don’t read like Solzhenitsyn or Koestler, but they wouldn’t be convincing if they did.

Though it probably wasn’t Griner’s main intent, the book dramatizes the stakes of certain geopolitical conflicts in the world—and the moral distinctions, often overlooked, between a flawed democracy, such as our own, and a relentless dictatorship.